- Product

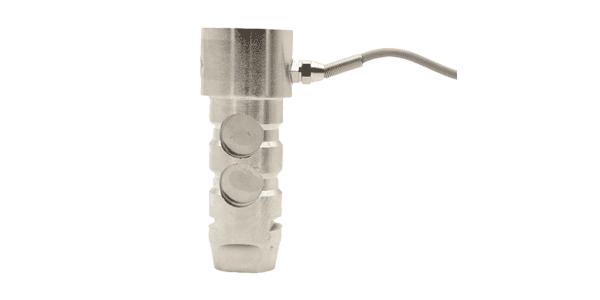

- Load Cell

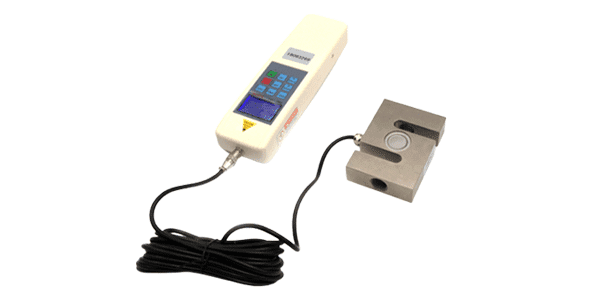

- Force Sensor

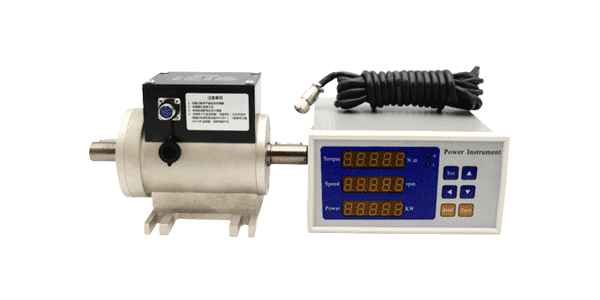

- Torque Sensor

- Dynamometer

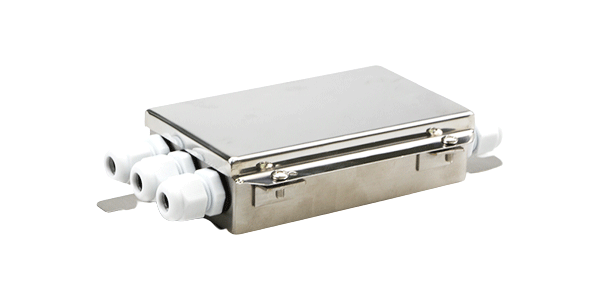

- Junction box

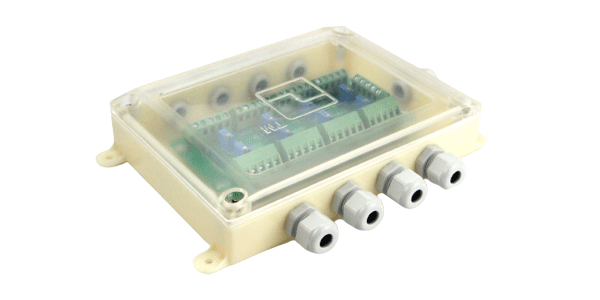

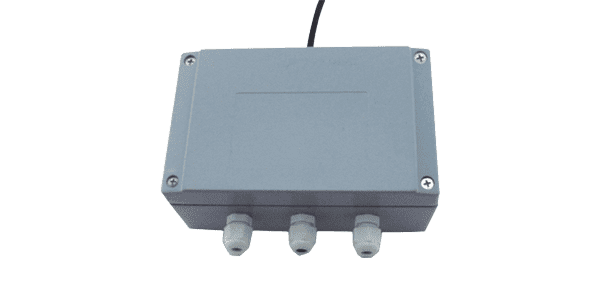

- Load cell amplifier

- Weight indicator

- Portable Truck Scale

- Crane scale

- Micro Load Cell Single Point Load Cell Planar beam load cell Digital Load Cell Shear Beam Load Cell Bellow beam load cell S type load cell Spoke type load cell Truck scale load cell Canister Load Cell Weigh Modules

-

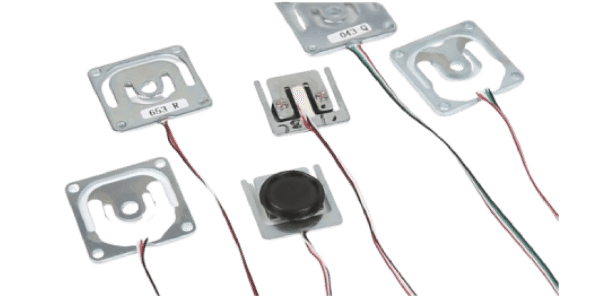

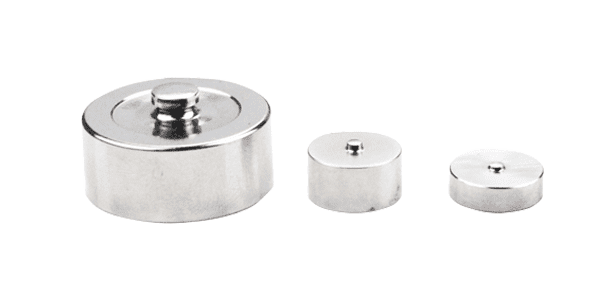

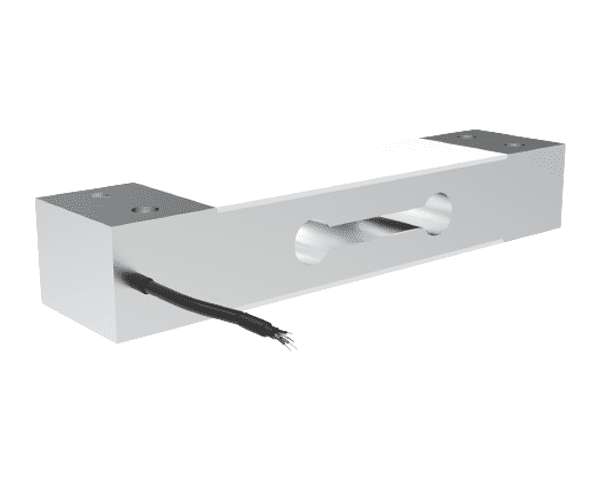

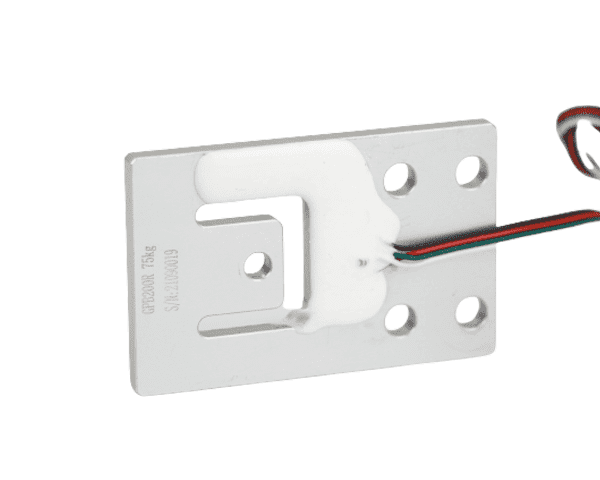

Micro Load Cell

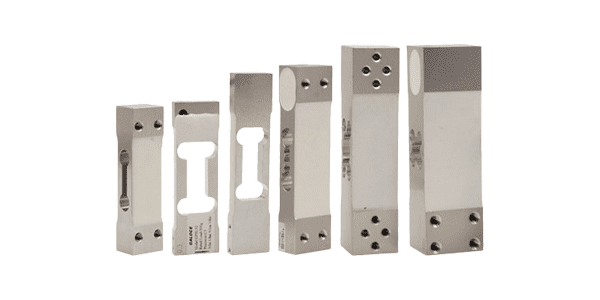

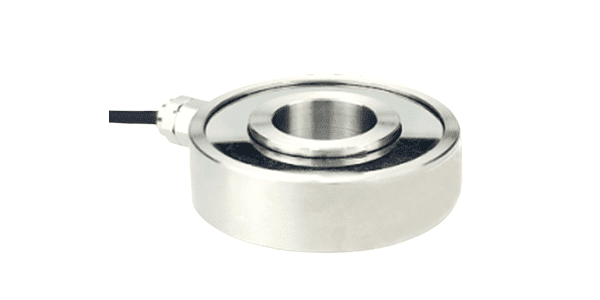

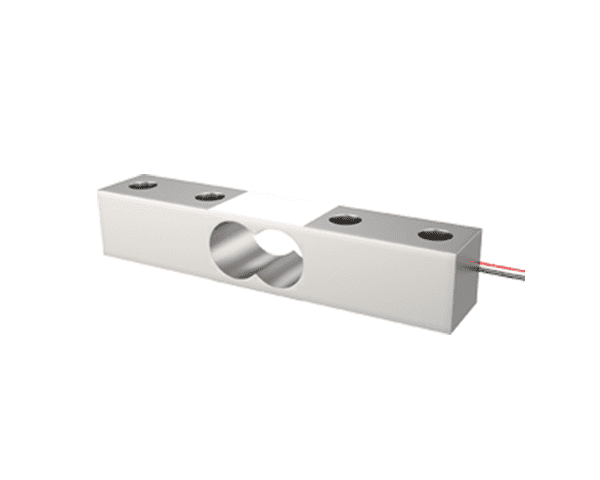

Single Point Load Cell

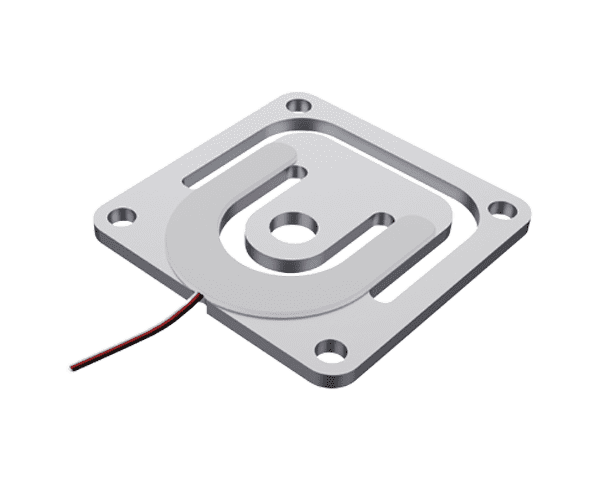

Planar beam load cell

Digital Load Cell

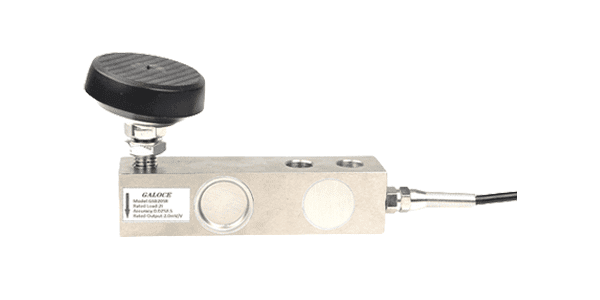

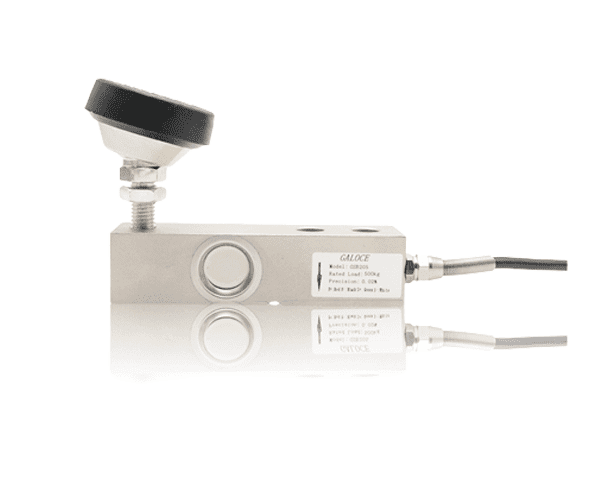

Shear Beam Load Cell

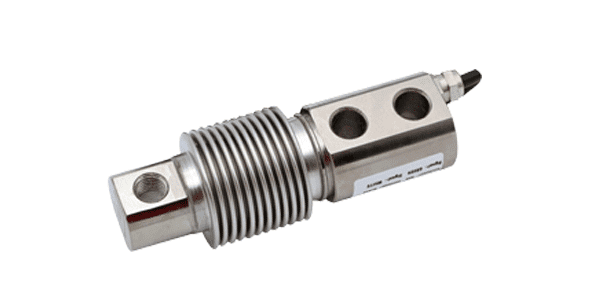

Bellow beam load cell

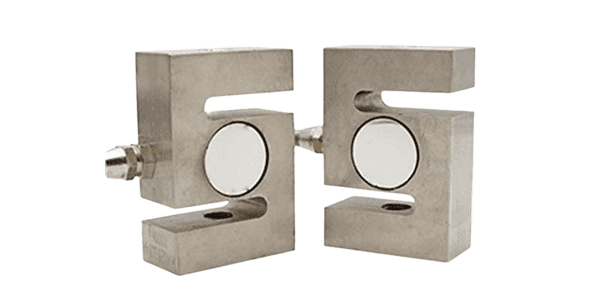

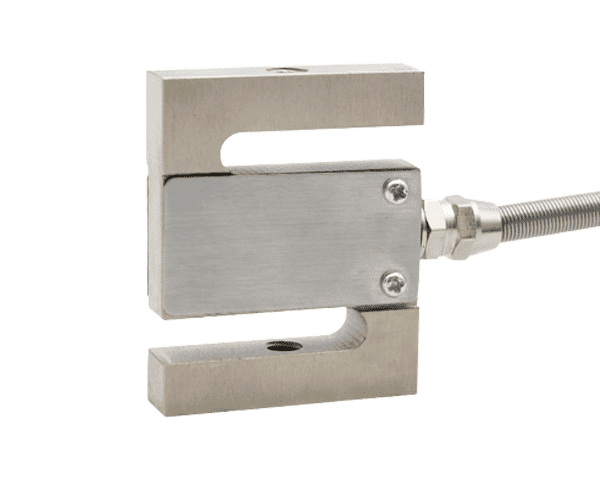

S type load cell

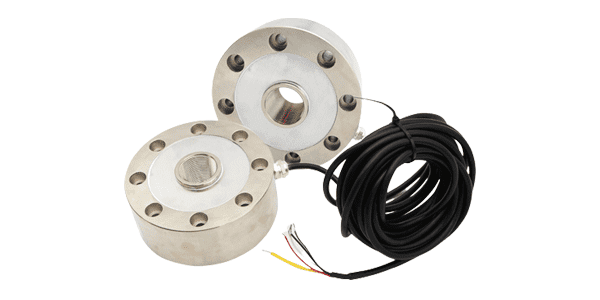

Spoke type load cell

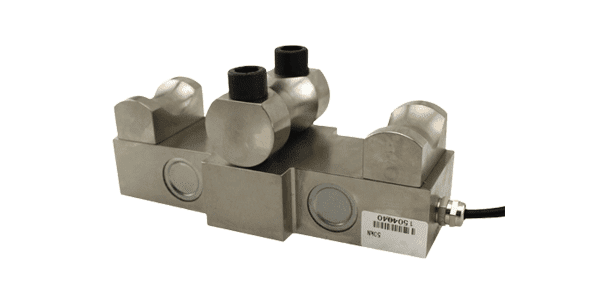

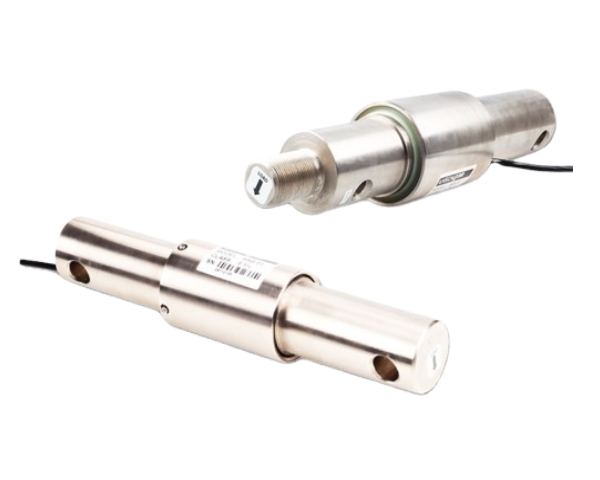

Truck scale load cell

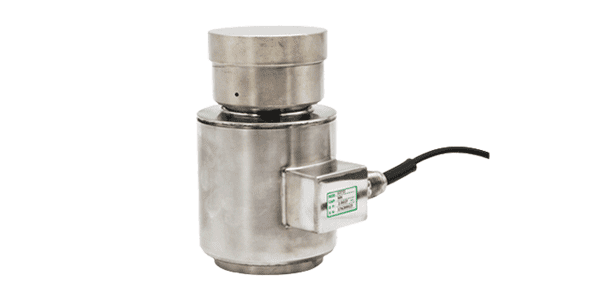

Canister Load Cell

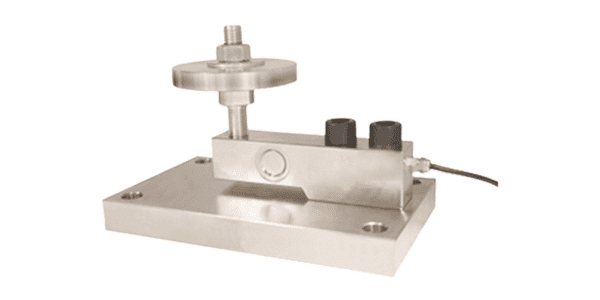

Weigh Modules

- Miniature load cell Force washers load cell Tension Compression load cell Three-axis load cell Rope tension load cell Load Pin Load Cell

-

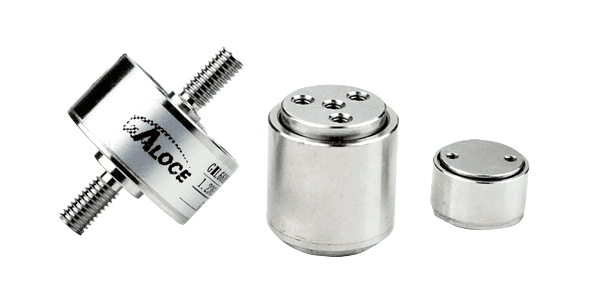

Miniature load cell

Force washers load cell

Tension Compression load cell

Three-axis load cell

Rope tension load cell

Load Pin Load Cell

- Stainless steel Junction box Plastic junction box Waterproof plastic junction box

-

Stainless steel Junction box

Plastic junction box

Waterproof plastic junction box

- Analog Weight transmitter Digital Weight transmitter Wireless transceiver

-

Analog Weight transmitter

Digital Weight transmitter

Wireless transceiver

- Platfrom scale indicator Truck scale indicator Belt scale indicator Weighing controller Torque meter Big screen

-

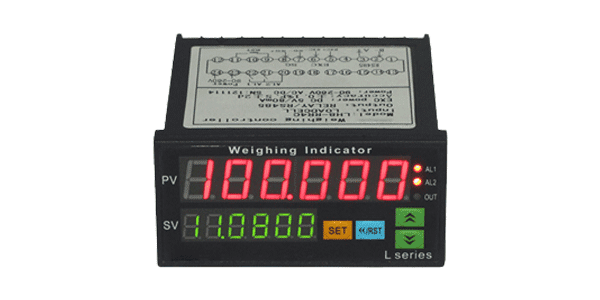

Platfrom scale indicator

Truck scale indicator

Belt scale indicator

Weighing controller

Torque meter

Big screen

- Solution

- Intelligence field Commercial scale Household Scales Transportation Medical field Agriculture machinery Construction machinery Industrial Process Control and Automation

-

Intelligence field

Commercial scale

Household Scales

Transportation

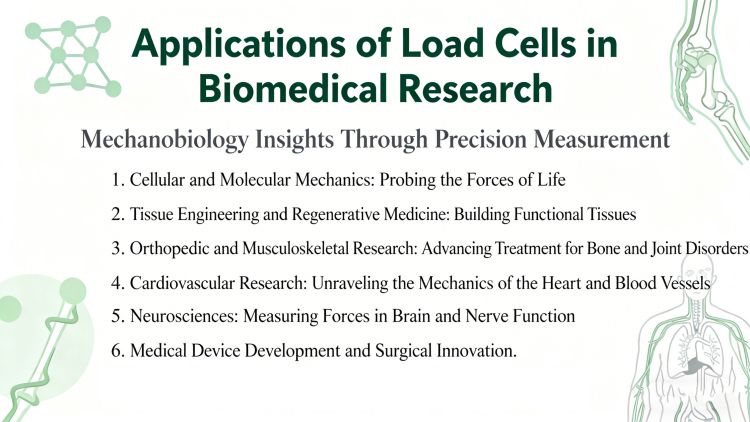

Medical field

Agriculture machinery

Construction machinery

Industrial Process Control and Automation

- Service

- Support

- IOT

- About us

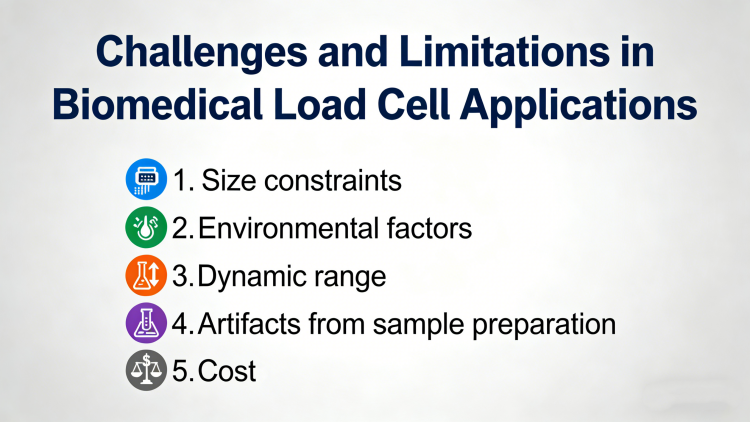

Despite their versatility, load cells face several challenges in biomedical research:

Despite their versatility, load cells face several challenges in biomedical research: